Saturday, April 23, 2022 /01:00AM/ By TheAnalyst, Proshare Research / Header Image Credit: World Grain

Nigeria has never been a major wheat producer, but neither had it historically consumed so much of the grain. Over the years the dinner and breakfast menus of Nigerian households have changed. Families have developed a sweet taste for wheat-based products. Global supply conditions have made bumped up the price of the commodity as demand outstrips supply. Global flour millers have had to contend with searingly high prices as consumers resist the upward tug on the cost of their daily meals.

Caressing a Crisis: Global Wheat

The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine has worsened what analysts and market observers already consider to be a global food crisis. Wheat prices remained high last year as a result of the combination of COVID-19-related disruptions and unfavourable weather. With the Russian-Ukrainian conflict threatening ship movement along the Black Sea, there has been a shortage of commodity supply and a persistent rise in the price of the crop.

Russia and Ukraine jointly account for 25% of the world's wheat export, a protracted war between both countries suggests a major weakness in global supply, which could see prices surge in months ahead.

Still reeling from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria's millers and bakers have once again come under intense cost pressures due to spiraling global inflation and reduced access to foreign exchange(FX). Reflecting difficulties caused by the current global energy crisis, Nigeria uses a large portion of its foreign currency reserves to support the import of premium motor spirit (PMS), thereby reducing the already meagre amount of foreign exchange reserves available to importers of wheat and other production inputs.

The lockdown of the economy in Q2 and Q3 2020, led to a massive disruption to flour supply chains. In 2015, the Global flour market was valued at US$200.50billion and was expected to reach US$243.94 billion by 2020, at the forecasted CAGR of 4.4%. However, amidst the COVID-19 crisis, the global market for flour in 2020 was estimated at only US$228.2 billion

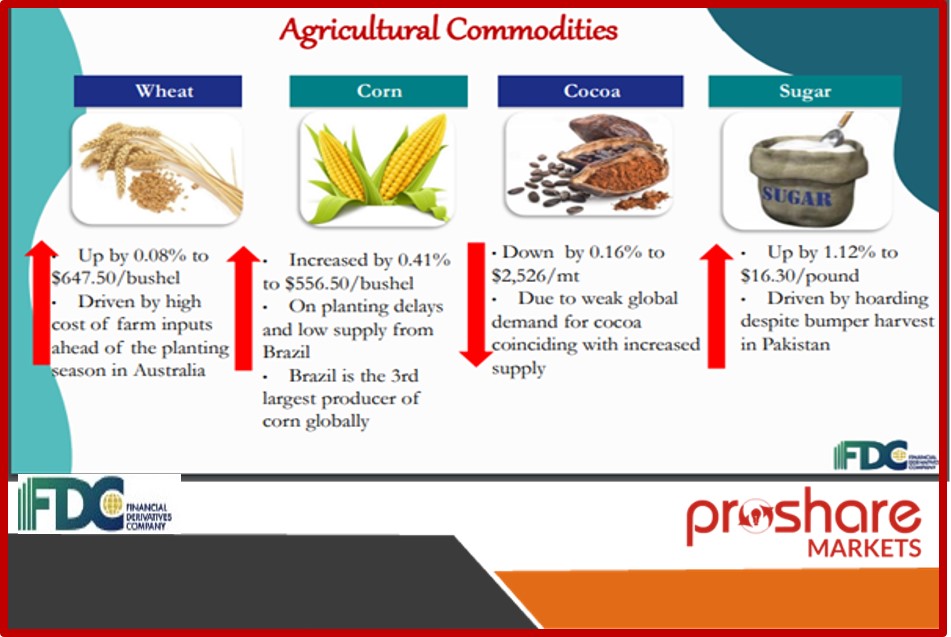

Consequently, the global wheat market saw average prices leap from US$560 per bushel in January 2020 to US$ 607 per bushel in November 2020 before sliding to US$577.25 per bushel in December 2020. Q1 2021 saw the price of wheat turn upwards as the wheat price rose to US$642 per bushel in January 2021 and US$650 per bushel in March 2021 as the price settled at US$726.75 per bushel in May. By June 2021, the price of wheat had dipped to US$693.5 per bushel. The upward trend has been sustained since the beginning of 2022, when the price shot above US$900 per bushel from $761.25 in January, pushing up to over US$1000 as of March 2022z (See chart 1 below).

Chart 1 The International Price of Wheat per Bushel January 2020 - March 2022

Source: Trading Economics

The biggest wheat exporters, on the other hand, have seen further increases in their free on board (FOB) prices. As of January 2022, prices rose in Argentina to US$303.75/tonnes; in Australia, prices rose to US$310.5/tonnes; Canada: US$401/tonnes; EU: US$322/tonnes; Russia: US$332.25/tonnes; and United States: US$321.13tonnes

It has not helped that these big suppliers' production, output, and exports have all witnessed significant drops across markets. Russia's output fell to 75.5MT in 2021 vs. 84.MT in 2020; Canada's production fell to 21.65 MT in 2021 vs. 35.18 MT in 2020. In the United States, production fell to 46.18MT in 2021 vs. 49.69 in 2020. The millers' plight was further worsened by the ever-increasing cost of freight. According to media reports from Q4, 2021, between 2015 and 2019, Nigerian businesses paid foreign shipping lines a total of US$45 billion (about N21.6 trillion) in freight costs.

The shippers' freight cost prediction for the end of June 2021 was roughly US$60 billion (about N28.8 trillion), assuming cargo throughput stays at the same level.

Since 2020, freight charges in Nigeria have risen. Shipping companies increased freight rates to Nigerian ports in January 2020, with increases ranging from US$1,500 to 1,140 Pounds or equivalent on all 20- and 40-foot containers. Due to a lack of empty containers, the freight charge for shipments from Europe and Asia to Lagos had reached an all-time high. From May 2021, rates rose from US$3,500 for a 40-foot container to US$13,500.

The demand for the wheat-based product being fairly price-elastic implies that the burden of every new rise in costs is primarily absorbed by the millers and bakers At the same time, a basket of similar commodities has increased in price by an average of over 50%, bread prices have only increased by 30%. The millers and bakers have borne the rest of the inflationary burden. Yet, a potential fair rise in the price of wheat and flour-based products in local markets can impose increased pressure on the earnings of the poor and socially vulnerable as bread represents a significant part of their daily diet. The same way other flour categories such as yam flour have equally experienced a hike in price, portending a challenging outlook in 2021 for producers of flour-based products and consumers, although to a lesser degree.

In its own case, the Senegalese government has always aided local crop farmers in the West African country's primary crops, such as peanuts, rice, millet, corn, and sorghum. In April 2020, Senegal's Ministry of Agriculture unveiled its Agricultural Program 2020/21. The program subsidizes producers' access to inputs (such as fertilizers, seeds, and phytosanitary products), as well as gives technical and marketing assistance to farmers. The Program budgets US$100 mn in 2020/21, with 40% going to fertilizer subsidies and 50% going to seed subsidies.

Has the 15% Wheat Levy been worth it? Developments in the Cassava Value chain

Following its introduction in July 2012, the 15% cassava levy imposed on wheat grain imports has raised the effective tax rate on the importation of wheat to about 27.5%, thereby raising the cost of millers significantly and diminishing their margins. The decision, which was part of a broader Cassava substitution/wheat import reduction strategy, was intended to encourage the usage of Cassava as an alternative to wheat flour. Amidst other objectives, the plan was supposed to finance the Cassava Bread Development Fund, which would support research and development efforts on cassava bread, and support master bakers to acquire new equipment for the production of cassava bread, most likely notably to boost cassava production.

Although Nigeria and four other countries, namely Brazil, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Congo DR, account for 70% of global Cassava, the FAO noted that a low level of mechanization almost entirely characterises cassava production in Nigeria. By implication Nigeria's output of HQCF (which is more refined than traditionally processed cassava flour-like Garri) is low. High farm gate prices of fresh cassava roots also make high-quality cassava flour (HQCF), starch, and other derivatives too expensive compared to imported options from Thailand and Vietnam.

In pursuit of a less wheat-dependent flour value chain and to exploit the country's natural endowment in Cassava, the government intended to increase the production of Cassava and HQCF. According to the plan, six high cassava processing plants capable of producing 40 metric tonnes of High-Quality Cassava Flour per day in the six geopolitical zones were meant to be established to provide flour millers and bakers with an alternative to wheat. This has yet to be implemented.

Essentially, since the introduction of the cassava substitution policy, there has been no significant improvement in the cassava value chain. Stakeholders have blamed the stagnation on the lack of political will, Poor Transport and Communications infrastructure, Cost of delivery to factory gate/distant commercial farms. Cassava has barely offered an alternative to wheat. Likewise, following the failure of the government to provide equipment for Bakers as stipulated under the Cassava development fund, bakers argue that their current equipment and machinery can only support the baking of wheat flour bread.

At any rate, the minor improvements recorded in the production of Cassava in recent months are attributable to the Anchor Borrowers Programme (ABP) and less associated with the Wheat Import Levy.

A Case for the Removal of the 15% Levy

In the light of the current crisis in Ukraine and the global food crisis that it has caused, the Nigerian government must reconsider the removal of the 15% wheat import levy. This is necessary to prevent a wider supply chain breakdown and recession. At this current rate of price growth, the cost of wheat importation may be up by a factor of two in just one year by July. If the government fails to support imports by removing the wheat import levy, the inflationary impact would be severe.

Given also the fact that the impact of the 15% wheat import levy had all along not been felt in terms of significant improvement in yield, Analysts and Market observers are of the view that the government needs to take a second look at the disruptive levy, which has in no small measure increased cost along with the flour milling and bakery value chain. Being a group of pretty inelastic commodities, the deadweight loss arising from the levy diminishes consumer surplus just as it does to producer surplus, albeit to a lesser degree.

Chart 2: The Deadweight Loss due to the Current 15% Levy on the Flour-based Market

Source: Proshare Research

Chart 3: Impact of Levy removal on the Wheat Value Chain

Source: Proshare Research

The deadweight loss arising from the 15% levy on wheat import pushes supply and demand to a lower equilibrium while imposing a higher cost on the market borne partly by the producers and consumers. Given that 75% of Nigerian households have bread and other wheat-based product as part of their daily meal, higher prices imply a higher cost of living and lower savings. The ricocheting economic effect is high inflation, slower growth, unemployment, a higher misery index, and social restiveness. As for millers, who also tend to bear part of the cost, they have to adjust their plant sizes, reduce their investment, and lay off some staff. The overall effect of the wheat tax has been disruptive and, as such, needs a rethink.

In a recent interview, the National Secretary-General of the Association of Master Bakers and Caterers of Nigeria (ABCON) noted that: "We had earlier made a plea to the government to cancel the 15% wheat (Cassava) levy. The levy was introduced in 2012 to create money for the cassava cultivation fund to enable bakers to produce wheat/cassava composite bread. The implementation of this project was not strictly followed. It has currently been abandoned. By 2016, 5,000 baking houses were supposed to have been supported or equipped. But as we speak, just about 157 of our members have benefitted from the scheme".

The Secretary-General further observed that "The former Government launched a Cassava-Wheat Composite Flour for Bread policy. And the millers started producing the new flour that contained some percentage of Cassava. But no sooner than the previous government left, the scheme was scrapped. Cassava flour disappeared from the market, and we continued to bake only with wheat flour.

"But recently, we were invited by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture in a bid to rescue the project. The MoU that was the binding document or principle under which the project was running is being renewed. The stakeholders attended the meeting held on October 26, 2021, at the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. We expect that this time, we would do things properly to avoid the looming danger to our industry and national food security and sufficiency".

Access to FX at the I&E FX Window

In 2021, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) decided to restrict millers' access to dollars to import grains, including wheat, by including the essential crop on the FX restriction list. The foreign currency restriction placed the millers in an impossible position to ensure a steady supply of milled grains despite the severe domestic supply shortage.

This has meant that millers have had to look for alternative sources of foreign exchange, which has led to them paying exchange rate premiums above the official import & export (I&E) window rate. The rise in the exchange rate has steadily whittled down operating margins and crushed underlying business profitability. The differential rate between the official window and the parallel market rate is approaching 40%. The disparity represents the exchange rate pass-through effect which implies additional cost to the millers, thereby discouraging additional investment.

Nigeria's FX reserves rely heavily on crude oil sales. Last year, crude oil price swings adversely affected the country's foreign reserves. Nigeria's foreign reserves had tumbled downwards since April 2021, when it settled at US$33.42bn before slumping to a 13-month low in July 2021, at US$33.33bn. Asides a blip towards the end of last year, the downward trend has been sustained. As of the end of February 2022, Nigeria's foreign reserve fell by 0.44 percent to $39.86 billion, down from $40.04 billion the previous month.

Overall, there remains an FX-induced increase in millers, food manufacturers, and bakers' cost of production. Nigerian millers and bakers have strenuously fought to keep prices stable. However, under the present circumstances, anyone can guess how much longer they can keep prices moderate.

Food Inflation

Analysts note that despite the fall in Nigeria's food inflation in 2021 which mirrored the decline in headline inflation rates the costs of wheat rose quarter-on-quarter (Q-o-Q) in 2021. The sustained rise in the cost of wheat has kept domestic food inflation higher than 17%. Market observers had expected food inflation to drop in 2022 following the bumper harvest of other grains at the end of 2021.

Despite the opening of the land borders in 2021, the country's food inflation fell by only 5.59 percentage points from 22.72% in April 2021 to 17.13% in December last year, analysts noted that lower wheat prices could have resulted in a much better, single digit food inflation. Economists had observed that despite the fall in food inflation, the price paid by Nigerians for wheat-based food remained high (caused by the rise in international wheat price and the higher local tariff). For instance, the cost of bread and other baked items recorded a 30% increase year-on-year (Y-o-Y) in 2021, supplanting the rise in the overall food index between 2020 and January 2022 (See Chart 4 below).

Chart 4: The Impact of Rising Cost of Wheat Import on Food Inflation

Source: Proshare Research

Bakers believe that the global cost of wheat would persist long after the Russian-Ukraine conflict. Therefore, if the country's wheat levy stays at 15%, and the naira continues to depreciate, with the problem of Cargo clearing logistics left unaddressed, food costs would remain high.

Promises of a Brown Revolution: Pie in the Sky?

Styled along the lines of the 1960 Indian Green Revolution, Nigeria's Brown Revolution has focused on addressing the dependence of local flour millers on imported wheat. Official data shows that up to US$2bn goes annually into importing five million metric tonnes of grain. Domestic production comes to 63,000 tonnesnes or one percent of the six million tonnes of annual consumption. The Brown Revolution is an initiative that attempts to improve upon past efforts using high-yield seed varieties and better agronomic practices to improve output per hectare.

While unveiling the first-ever rain-fed wheat programme at the CBN-ABP Wheat Seed Multiplication Farm, last year, the Governor of the CBN said the Brown Revolution hopes to reduce importation by 60% in two years. The programme is also expected to eliminate wheat importation or reduce its share of Nigeria's import bill in three years. The revolution also plans to cultivate 1.8m2 of land and bring 16 more states onto the programme.

The CBN has set out a plan involving the following actions:

Seed multiplication and establishing seed ripple centers. Apart from this, the expansion of the total hectare of land set aside for wheat cultivation to a capacity that can generate enough to meet domestic demand. The early gains recorded from the revolution have increased the national stock of high-yield seeds variety to about 20,000 metric tonnes. In the same vein, the CBN has, through a collaboration with a significant partner- Flour Mills of Nigeria, trained over 100 Nigerians as Extension service officers on practical best practices on wheat production. The recently launched project is the first wet season cultivation making two wheat crop cycles contrary to the widely held belief that cultivation only occurs in the dry season. According to the CBN, the country could add 750,000mt of wheat in a single year. There are plans to add to the current cultivation areas in Plateau state, Mambila in Taraba state, Obudu in Cross River state, and new in Kogi, Kwara, and Northern Oyo state.

A memorandum of agreement (MoU) was signed to guarantee offtake by the Wheat Farmers Association of Nigeria WFAN, FMAN, and AFEX (commodities exchange) to reduce market risk.

The Macroeconomy of a Flour Bust

Economy

The Nigerian economy fell into a recession in the third quarter (Q3) of 2020, after the country's aggregate output contracted for two consecutive quarters, -6.1% in Q2 and -3.6% in Q3 2020. In the first half of 2021, the economy witnessed consistent growth, growing by 0.51% in Q1 and 5.01% in Q2 of 2021. Subsequently, the positive growth was sustained in Q3 and Q4 2021 with 4.03% and 3.98% growth rates recorded respectively. Overall, the Nigerian economy grew by 3.40% in 2021.

Economists note that fiscal policy was expansionary in 2021, with the federal government initiating several Targeted Credit Facilities (TCFs) to cushion the adverse effects of the coronavirus pandemic on businesses and households. Indeed, manufacturers have had to contend with higher import excise duty and the naira depreciation. Hence, the complex combination of macroeconomic factors adversely affecting the grain millers could lead to a major food crisis in the months ahead as millers find it increasingly challenging to sustain breakeven production levels.

Impact of the commodities market/crude oil price

Market analysts note that crude oil prices have risen since November 2020, climbing to as high as US$96 per barrel in January 2022. The rise in crude oil prices has fed into the rise in diesel price, representing a significant cost item for flour millers and bakers. The rise in diesel costs has adversely affected consumers' real income. Consumers spend part of their regular earnings on cooking gas and kerosene. The rally in international crude oil prices puts pressure on the domestic cost of white oils in Nigeria and hurts consumer spending.

Kneading a Flour Bust

Nigeria has 21 flour millers, about a third of which own 80% of the market share, which suggests that the market, similar to the cement industry, is an oligopoly or a market with few suppliers. The market is also characterized by:

i) Climate Dependency

Although cultivated under different climates and soil types, wheat is best suited to temperate regions with rainfall between 30 and 90 cm (12 and 36 inches). Nigeria, however, is a tropical country. Despite the best efforts of the millers in trials to match seed varieties with soil types to establish new heat resistant and tolerant seed varieties of wheat in the country, Nigeria will probably never be able to cultivate wheat at a commercially viable, profitable quantity and yield. Attaining the production levels or yields of global wheat production leaders like China, India, Russia, and the United States is a tough act to follow.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) report in March 2022. The total wheat sown area in these top four wheat-producing countries in 2020/2021 was India: 31.4; Russia: 28.7; China: 23.4; US: 14.9 (mln ha), respectively. While production stood at; India: 107.9; Russia: 85.4; China: 134.33US: 49.7 (mln t) for the same period. In February 2021, preliminary measures suggest modest improvement in terms of area cultivated in the 2021/22 season. In India, Russia, China and the US area cultivated had risen to 31.62, 27.60, 23.57, and 15.04 (mln ha), respectively, while production was 109.5, 75.5, 136.9, and 44.8 (mln t) respectively, indicating a slump in the production of Russia and the US. Meanwhile, according to the Lake Chad Research Institute(LCRI) only 0.15(mln ha) of wheat has been cultivated in Nigeria.

ii) Relative Product Scarcity

The total domestic wheat production in 2020 was about 200,000 metric tonnes, which was less than the expected volume due to unfavourable weather conditions and poor seed varieties. Apart from being grossly insufficient to meet demand, local wheat lacks gluten quality in bread-making flour. As a result, flour millers have to bridge the support gap with an average of 4.7 million tonnes of imported wheat annually. Meanwhile, the Flour Milling Association of Nigeria (FMAN) has made extensive investments in several programmes to bridge this gap with a local alternative in the medium to long term. Presently, an estimated N500 million is invested by FMAN annually in critical areas of need and developmental programmes, including seed trials, research, training of smallholder wheat farmers, and funding the various farming research institutes in the country to ensure that the current local production levels of wheat improve significantly. The following are a few of these programmes:

The FMAN out-growers initiative under the Federal Government Wheat Acceleration Scheme in the 2020/21 farming season will provide input loans to the benefiting farmers. In February, the Flour Milling Association of Nigeria (FMAN) announced that in line with its mandate it has provided support to 150,000 farmers to speed up wheat cultivation in 15 states in the country. Dr. Aliyu Samaila, FMAN National Program Manager, Wheat Development Project, noted in February 2022 that the FMAN wheat program is being implemented under the Anchor Borrower Program (APB).

Also as part of the plan, Wheat Farmers Service Centres are planned in 15 Local Government Areas in the wheat-growing belts of Kano, Jigawa, and Kebbi state, where farmers would be trained on modern method of threshing of wheat, while at the same time increasing the direct offtake for the 5,000 farmers involved in the out-growers programme.

iii) Elasticity of Demand

The demand for flour-based products is price elastic, implying industry participants strife to keep costs moderate.

New Thoughts on Old Problems

Existing systems must be overhauled so as to be able to handle the wheat and general grain production challenge in Nigeria. The market is crucial, it must be developed. A few modifications, reshaping, and redirection of market regulation are required for the Brown Revolution to succeed. Likewise, ensuring security along the Sahel belt must be treated as a top priority to encourage farmers to return to farming.

The federal government must improve surveillance of farming communities through the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to conduct periodic fly-bys and take images of the area in order to determine whether marauders are active and provide early warning to farmers. As these efforts take place, the government and private sector actors might collaborate to create strategic silos across the belt and establish a price guarantee plan that protects crop growers from price fluctuations caused by unforeseen circumstances (floods, storms, insect attacks, etc.).

Asides from beefing up security around the country, especially in wheat cultivation areas such as Borno and Lake Chad region, plans to improve wheat production must include short, medium, and long-term strategic interventions which would include, but would not be limited to:

Short-term

- Giving millers access to foreign exchange at the I&E window to supplement domestic production that would remain inadequate for three years.

- Ensure that unscrupulous business interests do not intercept the (5%) CBN facility provided under the brown revolution

- Helping local farmers buy improved wheat seed varieties with the benefit of extension support

Medium-term

- Revisiting the strategic national grain plan to increase and hasten local grain production.

- Providing extension support on improved grain varieties through collaboration with local and foreign grain institutes.

- Allowing tax concessions that ply along with predetermined backward integration programmes (BIPs) with stated sunset clauses and annual local output targets. Failure to meet targets would attract a reversal of concessions.

- Government should provide the infrastructure to help millers reduce logistic costs along distribution corridors which may be achieved through digital supply chain monitoring and management across states and markets.

Local Agronomists have called on both subnational and federal governments to act decisively. They have requested the communication of clear goals and objectives, insisting that achieving self-sufficiency in wheat production would not happen because we desire it but because we have planned it using identifiable and measurable milestones. They note that the difference between failure and success is not a sultry romance with a chance but the design of a business case riding on the back of deliberate action.

Lagos, NG • GMT +1

Lagos, NG • GMT +1

592 views

592 views

Sponsored Ad

Sponsored Ad

Advertise with Us

Advertise with Us