"Banking is a very good business if you don't do anything dumb." - Warren Buffett

Introduction: All About Models - The Old vs The New

Nigeria's banking industry has swung from one model to another between 1999 and 2022. From universal banking in 1999, it steered towards the old, specialized banking model before the recent hard brake reset sent the sector into a more contemporary 'Holding Company (Holdco)' mode. The new banking structure mixes specialized banks like investment and merchant banks with a universal banking-like feature condensed into Holdco structures.

In simpler days, banks gained respect by their asset sizes; tier 1 banks would be banks with the largest assets above the industry's median asset value. Today, asset or share capital size would be inadequate to determine whether a bank was tier 1 or 2. The measuring tape has increasingly become elastic.

This report, therefore, critically appraises the extant approach to Tier based classification of Nigerian Banks and proffers a testable methodology as a credible alternative. This report notes that while there is no statutory guidance on the qualifying features of a Tier 1 bank, the Afrinvest Tier Based Classification of 2013, which produced the first-tier banks known by the moniker ‘FUGAZE’, has been widely adopted.

This is despite its over-emphasis on Assets and its failure to consider non-financial measures like governance. Nonetheless, such banks as have been classified as Tier 1 tend to edge out the so-called Tier 11 banks in big-ticket public and private-sector mandates to raise capital. Hence the need to ask questions about the very basis of the classification.

Following detailed research and investigation conducted over 180 days, Proshare analysts have developed the Proshare Bank Strength Index (PBSI) an aggregate index that selects, weighs, and sums the most important determinant of long-term profitability. Before now, the emphasis all along has been on the size of a bank's total assets, the PBSI lays more emphasis on efficiency metrics such as the quality of the loans and advances on its books.

The meaning is that even though a bank has large total assets on its statement of financial position, this would not count for much in assessing its tier 1 credentials if most of its loan assets are doubtful or of bad quality. Tier 1 banks should have good quality loan assets unimpaired by losses. These assets should be within the top 70 percentile of total unimpaired industry loans.

The proposed criteria are yet to be standard fare amongst Nigerian banks. However, Proshare analysts believe that this kind of measure or one expanded to cater to operational and managerial considerations would be better than simply looking at asset size, tier 1 capital, or adopting a loose notion of who belongs and does not belong to the tier 1 banking category.

By the old approach, which is essentially asset-based, and which selects pre-qualifying metrics rather arbitrarily, the banks that make up the moniker ‘FUGAZE’ retain their positions as tier 1 banks in 2021. Access bank leads the pack with an asset size of N11.73tr, then ETI (N11.69tr), Zenith (N9.45tr), UBA (N8.50tr), FBNH, and GTB complete the list of first-tier banks having recorded assets in excess of the N5tr cut-off. This would however presume that the aforementioned banks all met the pre-qualifying conditions (see table 1 below).

Table 1: 2021 Ranking – The Afrinvest Paradigm (Old Model)

By the PBSI calibration, however, FBNH and ETI exit the tier 1 category, while Fidelity Bank and Stanbic make a first-time entry into the class of first-tier banks. But this doesn’t come as a surprise, since both FBNH and ETI recorded NPLRs over the 5% threshold and would in fact be technically regarded as Tier 11 banks even under the old paradigm.

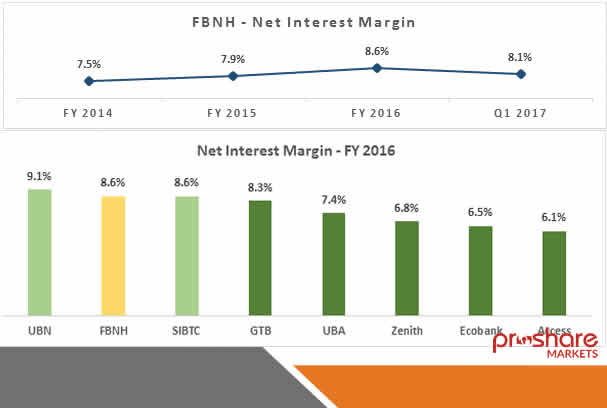

The result is an index that ranks Nigerian banks based on their aggregate points from CAR, NPL, LR, and Board’s Gender Mix (a proxy of Governance). These performance ratios were selected after querying half a dozen other variables namely: Assets Size (Ass), Gross Earnings (GRE), Net Interest Margin (NIM), Cost to Income Ratio (CIR), Digital Earnings, Loans to Deposit Ratio (LDR) Cost of Risk (CoR) and Ratio of Non-executive-to total directors (see table 2 below).

Table 2: 2021 Ranking – The Proshare Paradigm (New Model)

One important observation Proshare analysts made is the fact the bigger banks have generally maintained lower Loans to Deposit Ratio (LDR) and necessarily higher effective Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR). The fact that larger banks tend to have larger deposits means that a ranking based on LDR and effective CRR would be ab initio rigged against the bigger banks. Meanwhile, analysts have questioned the regulator’s frequent CRR debits which although seeks to penalize banks for not meeting their lending requirement but fails to take into consideration the fact that larger banks are in a catch-22 as they must also avoid exceeding the NPLR limits associated with creating risk assets in a bad economy.

Under pressure to lend, higher NPLs have been recorded industry-wide forcing the regulator to extend regulatory forbearance to the banks. This particularly played out during the COVID-19 global pandemic when subsequent international government actions affected bank loan assets worldwide. Supply chain disruptions, manufacturing furloughs, lockdown of cities, and restrictions on movements resulted in bank assets looking poorer than book values.

The COVID-19 virus hurt banks' profit and loss accounts between 2019 and 2021, resulting in slower loan asset expansion and reserve liability growth. The key features of Nigeria's banking sector over the last thirty-six months indicate that:

- Nigerian banks have recovered from their COVID-19-induced financial rut, hale and hearty. A return to modest growth (Nigeria's gross domestic product (GDP) fell by -1.92% in 2020 and grew 3.4% in 2021) has helped local financial lenders sustain profitability with lower-risk asset defaults.

- Despite large and growing shareholders' funds, local banks have posted minimal share capital. Liquidity has not been a problem for Nigerian banks as a global liquidity glut in 2021 made some inroads into the domestic money market. The sector's low non-performing loan ratios (NPLRs) have a bright side to the domestic banking narrative. Several banks listed on the Nigerian Exchange Limited (NGX) saw NPLRs settle below 5%.

- The sector, however, faces a slow growth risk in 2022. Proshare forecasts that GDP growth in the year will be between 2.5% and 2.7%, or 0.3% lower than Fitch Solutions 2022 forecast of 3%. The slow economic growth expectations would cycle into slower growth of gross bank earnings and net interest margins.

A review of the Credit ratings of Nigerian banks shows that Stanbic IBTC and Zenith Bank received 2021 Fitch ratings of AAA(Prime) and AA- (High grade) respectively. Two Nigerian banks fall within Fitch’s upper-medium grade namely Access Bank and UBA. The meaning of this is that only Stanbic IBTC, Zenith, Access, and UBA, make the cut-off for Investment grade rating. GTB received a B rating, while Fidelity Bank and other Tier 11 lenders were rated B- (which Fitch considers to be in the highly speculative class). ETI got a similar rating as of May 2021. Other banks obtained a B- rating attributable to the adverse macro-economic conditions that affected the banking business in Nigeria in 2021 (see table 3 below).

Table 3: Credit Rating of Nigerian Banks in 2021

We note that the available data on bank ratings applies to different periods the Proshare Bank Strength Index (PSBI) for 2021 did not include credit ratings. However, the PBSI methodology would be updated to include bank credit ratings in a follow-up report in June 2022.

Banking Changing Complexion

In the last three decades, the Nigerian banking industry has run the gauntlet of subdued progress and frenzied expansion. Between 2000 and 2005, the universal banking model was tested and failed. Exuberant greed and managerial incompetence conspired to bring about the Soludo solution requiring family-owned banks to merge with bigger rivals or be taken over by more professionally run competitors. The then erstwhile Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) governor Chukwuma Soludo raised the share capital of banks from N2bn to N25bn and effectively chiseled down the number of deposit lending institutions from the number of banks from 89 to 25.

The Soludo potion for poor bank management was administered again when HRH Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, former Emir of Kano, became the CBN governor in 2010. Sanusi did not raise the share capital of banks' but insisted on higher standards of corporate governance and supported the second round of financial sector takeovers.

The Sanusi era reinforced the notion of tier 1 and tier 11 banking system competition. The perception was a carryover from the Soludo era, which created an inner circle of enormous banks surrounded by a galaxy of smaller competitors. Unfortunately, the CBN never defined a tier 1 and tier 11 bank, leading to a fluid interpretation of where particular banks belong.

More recently, under CBN governor Godwin Emefiele, tier 1 banks have been captured under FUGAZE, a collective acronym for FBNH, UBA, GTCO, Access Bank, Zenith Bank, and ETI. If the measure were market capitalization, one or two banks would be in and out of the categorization depending on share price movement. If the measurement were share capital, all the banks listed on the Nigerian Exchange Limited (NGX) have their share capital below the N25bn statutory minimum prescribed by the CBN. None would qualify as a tier 1 bank (see illustration 1 below).

Illustration 1: Nigeria’s Curved Ball Classification of Banks

Analysts have noted that size and profitability are different concepts. The largest banks by asset size are not necessarily the most profitable. So, neither asset size nor gross or net earnings are good enough measures to establish a bank's industry status (see chart 1 below).

Chart 1: A Snapshot of Bank’s Performance in 2021-2022

However, combining corporate performance criteria can roll into some indicative metrics of tier 1 or tier 11 banks. Proshare researchers have considered a set of compressed metrics that review a bank's cost-to-income ratio, loan-to-deposit ratio, non-performing loans ratio, and governance quality (using board members' meeting attendance performance and board gender mix as proxies. Multiple regression analysis showed that the more women appeared on a bank's board, the better its performance as measured by its return on equity (ROE). The explanation for this could be debated.). In contrast, asset and equity size become guard rails for assessing whether a bank is tier 1 or tier 11.

The earlier dashboard shows that a bank with the largest total assets is not necessarily the most profitable. In 2021 Access bank had the largest total assets of 11.73tn, but Zenith Bank posted the largest profit of N244.56bn. ETI was the second-largest bank by assets, but it was the fourth-largest by profit, posting a profit after tax (PAT) of N146.33bn. Zenith Bank was the third-largest bank in the country by asset size at N9.45trn, but it was equally the most profitable. FBNH was the fifth-largest bank by assets but was the seventh-largest with an after-tax profit of N40.85bn. The largest bank by assets after what has become known as the big six or FUGAZE was Fidelity Bank, with a total asset size of N3.29trn and profit after tax of N35.58bn.

In the financial services sector, economies of scope (average cost) and scale (quality and size of service delivery) are essential but not definitive in assessing a bank's tier 1 status. Asset or equity size alone is a poor measure of which bank is qualified to be a tier 1 bank. Proshare researchers argue in the report that a combination of metrics is needed to establish the size, board, and management quality of a deposit money bank (DMB) in determining its tier 1 status. They observed that banks propped up by CBN forbearance should not qualify as tier 1, regardless of their asset and deposit sizes. They argue that a tier 1 bank may not necessarily be a systemically important bank (SIB).

The analysts observed that the concept of a tier 1 bank and a SIB tend to be interchanged, although they require separation for clarity. The money market's principal regulator, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), recognizes that a systemically important bank (and tier 1 bank) needs to have large tier 1 capital. In addition, a tier 1 bank must avoid regulatory forbearance and meet a combination of metrics that places it in the 50th percentile of Proshare's proposed Bank Strength Index (PBSI).

A Remodelled World of Banking

The ice age ended, but rather than lead to the termination of the world, it brought about a new order, an order with novel dominant species of animals and fauna and revised expectations accompanied by freshly minted frustrations. As with the old ice age, so with the unfolding digital age. Banks are going into a dignified decline as banking enters an era of adaptation and innovation. Bankers’ unwilling to ride the new wave of agile, innovative, and flexible service delivery will wear their undergarments around their ankles as the fierce tide of technology reveals who is digitally naked and who is not. Buffett's perception of banking as an excellent business may require a rethink.

The new era of decentralized finance (DeFi) will reshape the way banks engage in financial intermediation. The latest banking platforms will enable digital payment and settlement of transactions speedily and interactively unhindered by time or space. Traditional deposit money banking days may be ending, but the digitally interactive banking days are well on their way. A shift in banking products, processes, and service delivery conduct would require a change in culture, capital, credit, and controls. These four Cs explain why some banks would become gainers, other losers, and many more, benchwarmers in the fierce battle for corporate sustainability.

The Culture Crusade

With banks seeing much more of their businesses going digital after the COVID-19 pandemic, corporate culture has changed. The Information Technology (IT) department has moved from being a corporate appendage for the maintenance of computer systems and networks to leading the charge to improve the customer's journey experiences. The head of IT needs to be part of the service delivery planning architecture from the beginning as customers' expectations rise and their patience with delays or imprecision. The higher quality demands and need for speed require a culture change. Financial service producers must rethink corporate culture to align with evolving customer expectations. Mobile devices are the new branch network, and bank service delivery must rest on these delivery channels to meet the customers' aspirations and desires. Holding back on meeting customer expectations could mean the difference between glaring success and an assured failure.

The Capital Consensus

If banks are to invest in long-term technology, they must shore up capital and invest in tech foundries to enable them to play at the cutting edge of emerging technology. The new capital size would support 'space' rather than 'place' expansion, with products steadily emerging from the bank's product and service pipeline that enables them to dominate areas of uncontested competitive advantage. Besides being a risk-protection mechanism, the capital size must be a service delivery catalyst. The bridge from capital to service is technology; banks will need to shore up capital as they make a play for service excellence. One way of going about this is the Access Bank way. The bank has not been sterling in dividend payouts. Still, it has used retained earnings to support inorganic expansion, resulting in one of the highest returns on shareholders' equity.

An unanswered question is why Nigerian DMBs have issued and paid-up share capital below the statutory minimum of N25bn for national banks and N50bn for banks with international operations and why the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has not called on the banks to shore up their share capital. Admittedly, most banks, except those in the lowest category of tier 111, have robust shareholders’ funds, but their share capital almost without exception falls short of the legally required minimum. Unity Bank Plc has one of the lowest shareholders’ funds in the industry with a negative value of N280bn and a share capital of N5.84bn.

The Credit Creed

Credit to customers will require a deeper and faster interface with technology, customer behaviour analysis, and past loan performance. Using Monto Carlo analytical techniques and standard forecasting tools, default probabilities depend more on statistical probabilities calculations. Banks will have to shorten the credit cycle and relax the loan decision-making process under guidance. It has known that Fintech platforms have already started to make this possible, but loan recovery rates are presently uninspiring. Defi may improve access to loans and other financial products such as investments and savings; however, a lot is required to protect customers from abuse and fraud. In addition, the credit side of the business raises concerns about the financial regulatory framework and the delinquent loan recovery process. There are concerns about the violation of an individual's privacy and the use of cyberbullying to recover customer debts.

Banks will need to avoid the abrasive approach to loan recovery by Fintech firms lacking credit risk experience and legitimate loan recovery methods. The banks must lead the digital lending landscape with better intelligence and superior cash flow collateralization methods. To be meaningful digital credit expansion should be at least 10% per annum. A second-tier bank like FCMB appears to be showing the way with its 2021 digital income, as digital revenue accounts for 12% of gross earnings. The rise in digital income as a proportion of gross earnings was off the back of a 33% rise in technology cost.

The Control Console

Banks are increasingly concerned about keeping their costs in check. Most banks have kept their cost of risk (CoR) below 3%. The tier 1 banks have generally kept their CoR below 1.5%. Tier 1 banks have also ensured they kept a lid over their loan defaults by seeing that loan delinquency rates do not rise above 5%. However, banks listed on the NGX saw non-performing loan ratios range between 0.70% (Sterling Bank Plc) and 6.25% (ETI) in 2021. The tier 1 bank NPLRs clustered around 4.8%, with Fidelity Bank as an outsider at 2.9%.

The big banks also drove down their cost-to-income ratios (CIRs); the average CIR for NGX-listed banks for 2021 was 64.56%, and the average CIR for FUGAZE banks was 57.83%, while tier 11 banks had a CIR of 71.27%. In other words, FUGAZE, as a shorthand approximation of tier 1 banks, had CIR metrics close to the preferred 55% (see illustration 2 below).

Illustration 2: The Four Cs of Nigeria's Banking Giants

Banks have begun to live a new reality within an era of rampant innovation, unforgiving competition, and unrelenting creativity. To walk along the stony path of corporate sustainability, executives need to break from corporate conventions and jaded customer value propositions without compromising standard operating procedures; in running the gauntlet of flexibility and agility, they must discover process precision and customer needs alignment.

Several analysts have noted that from now on, banking will become a set of 'commoditized' or standardized products and services represented by a series of binary commands of ones and zeroes. Banking will no longer be about gorgeous glass buildings and exquisite architectural murals, but about easy-to-understand instructions conveyed to intelligent computer programmes that provide real-time solutions to customers' problems. The implications are vast and just as they are powerful.

The commoditization of banking means that there will be less human involvement in banking services and product delivery. Still, more digital skills, riding on the back of marketing and selling activities, would be guided by big data algorithms and the prediction and interpretation of future customer preferences. Customer service delivery would be less of a hit-or-miss game of Russian Roulette and more of a carefully thought plan of customer service optimization through data analytics.

The lending process would depend less on expressed or innate biases or personality traits but on personal borrowing histories, spending habits, and repayment profiles that provide a vignette of customer behaviour and spending patterns. Therefore, establishing loan default probabilities with real-time, data-backed analytics would be easier and more precise. Banks would increasingly become curators of massive data for products and services as they improve customer experiential journeys.

No Room for Nomads

Going digital is not a choice but a standard. The thickening plot to use technology as an enabler of superior service delivery requires workers across banks to learn, unlearn, and relearn skills to make them fit-for-market. Digital nomads (those without functional digital skills) have a shrinking space to ply their trade in a world where online communication, interaction, and collaboration have become a second skin. The world is a stomping ground for digital natives (people who eat the internet and various spin-off applications for breakfast). Late adopters may be on the fringes of the expanding global digital workspace, implying weak access to more considerable operational capital, poor competitive market presence, and thinner operating margins. In places like banks and financial technology (fintech), digital technology applications and evolution will separate those at the top of the business pile from those at the bottom.

Improved global and local capital market liquidity resulting from large COVID-19-induced fiscal expenditure provided banks with increased liquidity between 2020 and 2021 but most of the added liquidity did not translate into increased equity capital. The faster-paced growth in technology relative to equity capital in recent times is ironic, as analysts expected businesses would recapitalize as a virus-induced change to work and social culture increased the need to upscale technology use.

The Banking Sector's Response to Change-The Bot Battles and Other Matters

Indeed, as noted in the previous paragraph, banks have not been lazy and have moved swiftly to push the technology needle forward. In a rough sense, the top-tier banks in Nigeria reflect the size of bank equity capital and the extent of their technology adoption. Nigeria's top-ranking banks, usually referred to as FUGAZE (FBNH, UBA, GTCO, Access Bank, Zenith Bank, and ETI), have adopted artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) as service add-ons (see illustration 3 below). However, to drive the customer experience of tomorrow forward, banks need to go beyond the whistles and bells of creating chatbot interfaces with customers to a rethinking of the overall business of banking in such a way as to align corporate operations to customer expectations. Being big would gradually be less important than agility, flexibility, and innovativeness.

Illustration 3: The Chatbot Evolution

However, analysts have noted that the physical size of banks might be of lesser importance in the future. The new concept of bank size (and competitive strength) has nothing to do with buildings and branches but with customer deposit size, tier 1 equity capital, subordinated liabilities, unimpaired loans and advances, and the volume/value of digital transactions.

The size that will matter in the business of finance of tomorrow will be customers, non-fixed assets, and sundry financial liabilities. The future bank cash centres and service branches will be in the palms of bank customers as they pivot towards a wholly digital lifestyle. The growth of technology in financial service delivery would not obliterate the importance of standard measures of bank size, but it would require viewing banking metrics through prisms. A few indicators will remain critical and provide insight into competing banking operations, but 'soft' issues such as the quality of a bank's board and risk-weighted assets would become of equal importance as the size of its tier 1 capital.

Experience has shown that several large tier 1 capital banks have found themselves in history's dumpster.

Building Banks Stronger and Better

The ranking of banks by their tier 1 capital alone is inadequate to determine whether a bank is a tier 1 bank or not. Research suggests that most countries do not organize their banks as either tier 1 or tier 11; they classify them as systemically important banks (SIBs) or non-systemically important banks (NSIBs). However, Nigeria has adopted a unique classification for its banks for ease of risk administration or peer comparison. Rather than adopt specific Credit Rating agency metrics, local regulators, bankers, and financial analysts have preferred a shadowy and imprecise notion of tier 1, tier 11, and tier 111 banks (the latter reflects banks with negative shareholders’ funds).

The size of a bank's tier 1 capital is indicative of its relative systemic importance, but it does not capture the essence of its stability, liquidity, and capital cushion. To capture these elements of a bank's operations would require a broader set of indicators. Without a clear Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) guidance on what a tier 1 and tier 11 bank is, Proshare proposes an Index of bank relative classification. The Index elements would include the size of tier 1 capital, the bank's capital adequacy ratio (CAR), the bank's cost to income ratio (CIR), the bank's liquidity ratio, and its proxy corporate governance measures. The proxy measures for governance include Board diversity (number of females to male Board members, ethnic composition, age, professional expertise), number of annual Board meetings held, and members' attendance.

Proshare's Weighted Bank Classification Index may provide a fresh perspective to categorizing banks and help in clarifying where they belong in different classes. For example, tier 1 banks would have a higher Index threshold than tier 11 banks. The tier 111 banks would likely have the leanest tier 1 capital while posting the poorest asset quality and liquidity positions (see illustration 4 below).

Illustration 4: The Proshare Bank Strength Index (PBSI)

In other global financial markets, tier 111 banks become liquidated, nationalized, or placed under a debt resolution company like AMCON. So why do they still exist in Nigeria? A variety of reasons explain the existence of Nigeria's third-tier banking institutions. The first is the salience of political influence. One of the country's present third-tier banks has two former presidents represented on its Board of Directors (BoDs). In the Nigerian context winding up this bank would be unthinkable. The second reason would be the interest of the CBN in ensuring that no bank goes into liquidation, sending a signal of systemic difficulties; this would be unacceptable to the local money market regulator. A third reason would be the instinctive dislike of failure, so bank managements try to do all they can to prevent their institutions from being put on the auction block or taken over by bigger competitors. For example, non-listed Heritage Bank has operated with negative shareholders’ funds for over three years without regulatory determination of its existence or a corporate takeover or recapitalization by a new investor. Heritage Bank is, therefore, one of those anomalies thrown up by the Nigerian financial system unwilling to accept liquidation or bankruptcy.

In the report, Proshare analysts conclude that Unity Bank's situation may not be as dire as Heritage Bank's, but it does throw up some ironies. The analysts noted that the bank was very liquid in 2021 despite its negative shareholders' capital which exceeded N250bn. The large deficit in its capital would suggest a narrower opportunity to transact business on the back of thin but growing deposits. Another queer fact, according to the report writers, was that at 0.03%, the bank had the industry's lowest non-performing loans ratio (NPLR). The reason was that the bank cleaned up its most toxic risk assets in 2018 by selling them to a factoring company at a deep discount, leaving its balance sheet derisked and loan-light. The removal of bad loans from the bank's balance sheet led to the shrinking of its capital and the creation of its negative shareholders' funds. On the positive side, the bank has had the cleanest risk assets in the industry, with the lowest non-performing loans ratio (NPLR) at 0.03% (see chart 2 below).

Chart 2: NPL Ratio of Nigerian Banks in 2021

However, negative shareholder funds are not the only reason tier 111 banks represent the bottom of the banking pile. Tier 111 lending institutions also have challenges with their interbank positions, liquidity, and cost-to-income ratios (CIRs). Unlike Unity Bank Plc, Heritage Bank, the second Nigerian bank with known negative shareholder funds, ticks all the boxes of a tier 111 deposit money bank (DMB).

While Unity bank is liquid, Heritage Bank Limited is not. Unity Bank Plc has a low NPL; Heritage Bank Limited has a high NPL. Unity Bank Plc has a negative equity base; Heritage Bank Limited equally has a negative equity base. While Unity Bank Plc turned a profit in financial year-end (FYE) 2020, Heritage Bank continued its longstanding loss. The two banks show the broad categories reflecting the differences between so-called tier 1 banks and others.

Strategy as a Toolkit

Does it matter whether a bank is tier 1 or tier 11? Yes, it does. A growing tribe of corporate analysts understands that ever-increasing bank capital, superior corporate governance, and strategic corporate intent separate banks into the top and other tiers. The stronger the bank capital and the more precise the strategic goals, the more likely it would grow its top and bottom-line earnings.

A tier 1 bank would likely attract big-ticket public and private-sector mandates to raise third-party capital either by debt or equity. A top-tier bank would equally attract large public and private sector deposits, enabling it to scale its business activities and increase market share and competitive advantage. The notion of skill dominating size is naïve. While skill is critical to resource allocation and management, it would still hit a brick wall if not allowed to feed into growth.

For example, in 2005, STB (erstwhile Standard Trust Bank) took over UBA (an arguably more significant bank by assets and deposits) because of its market savvy and ability to navigate the changing business landscape. Still, STB needed the UBA size, brand recognition, and loyalty to support a growth model that ensured sustainable profitability. Growing bigger was synonymous with getting better, but this is not a holy grail. A bank could become more prominent and poorer if its management were Peter principled or promoted to its highest level of incompetence due to growth. The unintended consequences of growth unaccompanied by managerial capacity partly explain why most of the 89 banks that operated in Nigeria in 2000 collapsed or were acquired.

However, analysts have observed that a few smaller banks that have rolled into larger ones (tier 1) have done well. Access Bank, for instance, is seen as a tier 1 bank and a member of Nigeria's elite FUGAZE (FBNH, UBA, GTCO, Access Bank, Zenith Bank, and ETI), a tribe of tier 1 lenders responsible for 80% of total industry deposits and 90% of industry assets. Access Bank has grown massively but inorganically by acquiring larger institutions such as Intercontinental Bank Plc (2011). It recently acquired Diamond Bank Plc (a merger in 2019). The rapid growth of Access Bank both nationally and continentally has underscored the power of being big and riding on clever game planning.

Strategy and survival are different sides of the same coin. Strategy is an effective survival tool for banks as a small band of service providers dominate the industry and set the tone for operating margins, technology, and profit. In other words, the banking industry revolves around a shopping list of six large banks, popularly called FUGAZE, and a merry band of smaller and sometimes friskier rivals.

On realizing their inability to speedily ramp up their brick-and-mortar infrastructure to take on their bigger rivals, smaller banks have opted to take the technology route as a counterpoise to the competitive dominance of the big six (see illustration 5 below).

Illustration 5: Nigeria's Changing Banking Sector Landscape

"small" is a relative term and viewed in the light of total asset size, loans and advances, and the size of a bank's customer deposits to industry averages. Interestingly, the research showed that the size of a bank's share capital is a poor measure of how large the bank's operations are. Most Nigerian banks have share capital below the CBN minimum requirement of N25bn for national banks and N50bn for international banking operations. To make for an easier comparison of capital strength, the report authors looked at the shareholders' funds of banks listed on the NGX. They discovered that using this criterion validates the notion of Nigeria's FUGAZE banks as tier 1 lending institutions, mainly if the bar is set for Nigerian deposit money banks with shareholders’ funds up to and above N700bn (see chart 3 below).

Chart 3: Shareholders Fund of Nigerian Banks in 2021

According to the report writers, Nigerian banks have relied more heavily on their reserves to shore their capital base rather than share capital. Indeed, all listed banks on the NGX have used statutory reserves, share revaluation reserves, retained earnings, and subordinated long-term debt to portray capital strength. None of this is illegal or technically incompetent. Still, the 2010 CBN law clearly states that for a bank to operate in Nigeria at the national level, it should have a minimum share capital of N25bn or N50bn for internationally operational deposit-taking institutions (see table 4 and illustration 6 below).

Table 4: Share Capital of Nigerian DMBs 2021

Illustration 6: CBN Minimum Share Capital Requirements for Nigerian DMBs

The banking game of size appears to be less constrained by the magnitude of bank equity than by the CBN-imposed loan to deposit ratio (LDR) of 65% and cash reserve ratio (CRR) of 27.5%. The statutory LDR has forced banks to grow messier loan assets or cut down on their deposit liabilities or loan portfolios, slowing operational growth or paying fines on their cash reserve deposits with the CBN. Strikingly, the LDR of a bank is a poor predictor of its status. Unity Bank has a negative shareholders fund and a small loan portfolio size but has the best loan-to-deposit ratio of all banks listed on the Nigerian Exchange Limited (NGX). Fidelity Bank has been viewed as a second-tier bank but has the second-highest loan-to-deposit (LDR) ratio of banks on the NGX. Proshare researchers discovered that currently perceived tier 1 banks appear to cluster in the middle of the LDR table, with Zenith Bank posting an LDR of 61.96%, Access Bank an LDR of 60.16%, FBNH an LDR of 51.09%, and ETI an LDR of 49.09%. Bigger banks by asset size seem to find it difficult to lend out their deposits (see chart 4 below).

Chart 4: LDR of Listed Banks on the NGX 2021-When Size Doesn't Matter

The problem appears to be that the larger the deposits, the more conservative the bank becomes in creating risk assets to prevent a rise in its non-performing loans ratio (NPLR). Most banks want to keep their NPLR below the 5% statutory threshold. Given this scenario, analysts agree that the CBN's discretionary CRR debits will continue throughout 2022 and put downward pressure on bank asset yields.

Coming to Terms with the Market

From the previous section, beyond the limitations to growth imposed by CBN's market regulation and the problems of operational size, will technology be enough to support bank profitability and sustainability? Not likely, say the report writers. While technology may enable smaller-sized banks to acquire more customers outside the traditional brick-and-mortar framework, economies of scale and scope still matter.

Larger banks have lower average operational costs than their smaller counterparts, giving them a generic strategic advantage. Banks like UBA, Zenith Bank, Access Bank, and ETI have lower cost-to-income ratios (CIRs) than Sterling Bank, FCMB, Fidelity, and Stanbic IBTC. An oddball is FBNH which has a CIR high (but falling) compared to other FUGAZE banks.

FBNH's cost-to-income ratio (CIR) has risen steadily in the last five years, rising from 47% in 2016 to 54% in 2017 before climbing to 63.4% in 2018. In 2019 the group struggled with operating costs as the CIR skipped to 69.7%. Since 2020 the bank's management has applied the breaks, with the bank's CIR stopping at 68.6% in 2020 (see chart 5 below).

Chart 5: FBNH-When Size and Costs Part Ways

Analysts have noted that a characteristic of large banks is that they muscle down on their costs to keep their CIR as close to 50% as possible. Proshare has developed a convenient but modifiable sustainability criterion involving a bank's CIR plus its cost of risk (CoR) plus its non-performing loan ratio (NPLR), the lower the combined ratio, the higher the prospects of operational sustainability, growth, and profitability. Proshare's research suggests that large banks would likely have ratios clustering around 0.50, while other banks would have ratios between 0.60 and 0.70. The higher the percentage, the more likely the bank would wander between tier 11 and tier 111 status.

'Blue Oceaning' Tier 1

Improving economies of scope (lower CIRs) and higher economies of scale (larger LDRs) are just two matters of concern to tier 1 banks. Another major tier 1 bank issue is the creation of islands of uncontested or mildly contested competitive service or product advantage.

For Tier 1 banks to survive in the upper financial service delivery league, they must break away from the constraints of banking as a commodity to banking as a unique service delivery experience and a bespoke product delivery pipeline. Fighting in highly contested markets will thin down net interest margins and flatten bank profitability, harming corporate sustainability.

Analysts believe top-tier banks can think and act differently but must find inspiration, imagination, and execution. Differentiating between corporate service quality and product delivery standards will be the primary separator between banks that succeed and banks that do not, as decentralized ledger technology (Blockchain) becomes an industry disruptor. Big banks can use economies of scope to reduce short- and long-run average operating costs, but this is meaningful only if a rise in corporate earnings accompanies it. Proceeding into the emerging banking battlefield of the mid to late 2020s will be a struggle for dominance in self-created market opportunities. The so-called 'white spaces' created by banks with tier 1 status should keep their financing costs low and operating incomes competitive (see illustration 7 below).

Illustration 7: The Economics of the Economies of Scope

The long-run average cost curve (LRAC) of tier 1 banks traditionally lies below their smaller industry counterparts, giving them cost advantages at higher service quality or larger service volume. The lower costs could show up in lower bank cost-to-income ratios (CIRs) of the FUGAZE. However, the data evidence does not sit tidily with this assumption as some FUGAZE banks have higher CIRs than their smaller competitors (see chart 6 below).

Chart 6: Nigerian Bank's Cost-to-Income Ratio (CIR) 2021

Fidelity Bank Plc had, as of 9months 2021, a CIR of 66.40% (64.90% in FY2021), which was lower than FBNH's CIR of 73.50%. The higher a bank's CIR, the more likely it would fall into the tier 11 bank category.

Proshare researchers also discovered that generic strategies like product and process differentiation, product and process focus, and cost-containment are essential but not conclusive or exhaustive. The report's authors noted that the traditional competitive approaches need to be boosted by pre-empting customer journey experiences and providing solutions that rely more on machine learning and artificial intelligence (ML/AI) than on standard products and services in the average bank's brick-and-mortar toolbox.

The writers noted that the banks need to stay ahead of individual and corporate needs and provide solutions that allow flexibility in either personal preferences or corporate aspirations. Bespoke structured finance facilities will become increasingly important as a service as corporate needs evolve. Banks would run head-to-head with the ascendancy of private and corporate banking as a service as organizations look for unique solutions that enable them to meet their customers' business objectives. In 2022 banks are expected to drive along specialized pathways more aggressively (see illustration 8 below).

Illustration 8: Critical Trends to Look for in Nigeria's Banking Sector 2022

For example, banks will need to service organizations with different characteristics, from start-ups to 'trapped' corporations, bureaucratic behemoths, and agile firms, large and small. The banks would need to assist companies in achieving their goals in an environment of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) (see illustration 9 below).

Illustration 9: Nigerian Banking Sector's Agility Matrix

Big banks can easily cherry-pick customers as they assist them in developing the capacity to grow new competencies, stronger competitiveness, and tougher corporate governance frameworks. The large tier 1 bank also has access to international and domestic liquidity unavailable to banks in the lower tiers.

The researchers noted that tier 1 banks seem to provide more customer-specific and needs-driven products and services to solve problems than their smaller counterparts. They observed that economies of scope in the sector allow tier 1 lenders to offer solutions to intricate customer problems much easier than their lower-tiered competitors.

The analysts equally noted that there is no problem with the concept of a tier 1 bank but with its classification. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) does not classify banks into tiers. The first time the concept of a tier 1 lending institution appeared in the local business lexicon was in a 2013 report of Afrinvest, an investment banking group previously run by Mr. Godwin Obaseki, the current governor of Edo State. The Afrinvest framework used four criteria to assess bank status. The criteria included asset size, capital adequacy ratio (CAR), liquidity, and non-performing loans (NPLs). Each criterion got a threshold metric with which banks were evaluated—above the threshold represented tier 1 and below tier 11.

In researching the objective criteria for bank tier 1 status, the analysts noted that the Nigerian banking regulator broadly classifies banks based on their scope of operation and systemic importance to the financial system. The well-known industry classification of banks into tier 1 and 2 is not a designation shared by the CBN but by market operators and the financial media. Notwithstanding, Proshare analysts' calibration of Nigerian banks using the CBN's assessment criteria revealed seven systemically important banks (SIBs). The SIBs were not necessarily first-tier banks, but all tier 1 banks were systemically important (see illustration 10 below).

Illustration 10: Understanding What it Means to be Systemically Important

Proshare's Bank Strength Index (PBSI) emerged from a pooled multiple regression analysis of bank operational indicators. The variables included total asset size, cost-to-income ratio (CIR), capital adequacy ratio (CAR), cost of risk ratio (CoR), and a few proxy management quality indicators, which set the framework for assessing which banks would fall into the different categories of tier 1, 2 and 3. The data for the Index comes from the year-ended December 2020 financial statements.

A fast and ready metric is the addition of the CIR, CoR, and NPLR, the higher the combined value, the lower a bank's rank. A bank with a combined score above 70.5% is classed as tier 11 and below 70.5% as tier 1. Applying the criteria and methodology to the NGX-listed banks in 2020, only six banks qualified as tier 1 banks; they were: GT Bank, StanbicIBTC, Zenith Bank, UBA, Access Bank, and Fidelity Bank. Surprisingly, FBNH and ETI were out of the top tier category, and, therefore, the notion that all the FUGAZE banks' approximate tier 1 banks were called into question (see table 5 below).

Table 5: The Fast and Ready Proshare Bank Strength Index (PBSI)

Stanbic IBTC, UBN, and Wema Bank CoR data were unavailable during the report writing period but taking the median value of the CoR of banks listed on the NGX would ascribe a value of 1.5% to the three banks. By applying this adjustment, the positions of the top banks would be unchanged, but Sterling Bank would climb above UBN in ranking. UBN would drop to 11 while Sterling BankQ would rise to 10. Using a 70.5 percentile would see the following banks fall into tier 1 territory: GTCO, Stanbic IBTC, Zenith Bank, UBA, Access Bank, and Fidelity Bank (see table 6 below).

Table 6: The Modified Fast and Ready Proshare Bank Strength Index (PBSI)

Section 1 of the report provides an understanding of the Global Banking Industry Structure and classification. The section also takes a helicopter view of the banking industry structure around the world, highlighting existing bank classifications, and their bases.

Section 2 looks at the evolution of the Nigerian banking ecosystem over the years and establishes the need for a regular review of the basis for tier-based bank classifications. The section reviews the need for strong banks and highlights their role in achieving financial inclusion and supporting economic growth. The section also takes a look at the distinguishing features of the top Nigerian banks under the existing classification of banks. The section discusses the impact of technology in reshaping Nigeria's financial markets and how concepts such as "open banking" will become of major importance in the future.

Section 3 zeros in on the banking regulators’ classification and designation of banks, highlighting the major forms of classifying banks globally and domestically. It analyzes the CBN systemically important banks (SIBs) and looked at the context of their operations and the calibration of their primary performance data. It also looks at the new Basel III rules for a global perspective on bank capital classification.

Section 4 presents the Proshare Bank Strength Index PSBI as an intuitive and reasoned alternative to the existing tier-based classification The PSBI methodology is later used to analyze and rank Nigerian banks into tiers 1 and 2.

Section 5 concludes with a panoramic view of the report. It summarizes the research outcome and gives insight into the implications for the banking sector. The report calls for the review of the tier 1 categorization of domestic banks annually. It points out that changes could occur to fundamental indicators making some banks fall into the status while others fall out. According to the writers, using a fixed notion of tier 1 banks (FUGAZE) is inequitable and leads to poor resource allocation. Certain financing opportunities or access to funds depend on banks' categorization; the tier 1 institutions have options unavailable to lower-ranked institutions and, therefore, have a competitive funding advantage.

The section suggests that for fairness, equity, and financial resource efficiency, banks listed on the NGX should be categorized into tiers 1 and 2. The formalization of the bank category would clear up the uncertainty surrounding the use of the grouping by international institutions in determining their relationship with domestic Nigerian deposit-taking lenders.

The researchers observed that although a bank may be systemically important, it may not necessarily be a tier 1 bank. While the complexity of a bank's linkage may make it essential to the financial system, a bank with less integral associations may result in minor contagion in a crisis. In other words, a systemically important bank and a tier 1 bank may not necessarily mean the same thing.

Downloadable Versions of Tier 1 Banks Report (PDF)

1. Executive Summary: Nigeria’s Banking Industry: The Case for Redefining Tier 1 Banks - May 28, 2022

2. Full Report: Nigeria’s Banking Industry: The Case for Redefining Tier 1 Banks - May 28, 2022

Lagos, NG • GMT +1

Lagos, NG • GMT +1

5703 views

5703 views

Sponsored Ad

Sponsored Ad

Advertise with Us

Advertise with Us